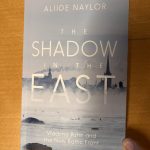

Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front

The Baltic countries are small: Estonia has 1.3 million people, Latvia has 2 million, and Lithuania 2.9 million. Historically torn between east and west, the Baltic states have in recent years faced the question of whether they are better off under potentially friendly relations between Trump and Putin or mired in the haze of a new Cold War.

In 2004 they joined NATO.

The Baltics are uniquely equipped with the challenges posed by modern Russia. Their proximity, history, and heightened exposure to the language and tactics of their eastern neighbors mean that they have a degree of expertise that the rest of the world could stand to benefit from in the present climate.

On 23 August 1989, some 2 million people in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania united against Soviet occupation. They stood in a seamless line stretching for more than 600 kilometers. In December 1989, the People’s Deputies Congress of the USSR finally declared the German-Soviet pact and its secret protocols legally null and void. Lithuania was the first to declare independence, on 11 March 1990.

Around 25 % of Estonia’s population are ethnic Russians, with a similar percentage in Latvia. In Lithuania, the split is much smaller 5.8 percent. But there are more Poles 6.6 percent.

According to stereotypes Estonians are slow and reserved, Latvians are the worst for Russians and have six toes, and Lithuanians are basketball fanatics. Latvian and Lithuanian have Indo-European language roots, Estonia’s is Finno-Ugric. They remained pagan until the 14th century.

The Russian Empire absorbed the Estonian and Livonian areas in the 18th century after the Great Northern War.

Estonian scholar Vello Pettai identifies five different commonalities present in the struggle for independence from the Soviet Union: environmental mobilization, calendar demonstration, intellectuals’ leadership, organized movements, and personal changes.

Putin is not only popular inside Russia. He is also something of a symbol of rebellion internationally and even enjoys a degree of popularity inside the Baltic states.

The stream of propaganda being pumped out by internal Russian outlets relating to the Baltic states, namely that they are NATO puppets, full of Nazi sympathizers, and subjugate their Russian-speaking population.

The shadow of the past

If you scratch any Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian of the older generation, and you ask them who was worse – the Soviets or the Nazis – the Soviets were way, way worse.

There were two Soviet occupations of the Baltic states: the first in 1940-1, and the second from June 1944 which lasted until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The Soviet mass deportations saw at least 200.000 people forcibly removed from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. There were two operations. Operation Priboi (Coastal Surf) in March 1949 (90.000 deported). Operation Vesna (Spring) in 1948 affected only Lithuania.

The Baltics were home to several concentration camps. The Jewish population across the Baltics was decimated. Every year, some 1.500 – 3.000 men participate in a Latvian Waffen SS veterans’ march in Riga.

Jonas Noreika, or General Storm, was a national hero in Lithuania. It was his daughter that started to explore his Nazi past in 2018. She found out that he was involved in the murders of over 14.000 Jews.

The Baltics are an important example of the extent to which the Soviet Union relied on fear as a method of social control, and what can be achieved if this fear is overcome.

The majority of Soviet monuments were removed from Baltic countries or at least moved into away locations. All of them also have some occupation museums, that remind them of Soviet times.

Raimundas Karoblis, Lithuanian Defense Minister, is saying that Russia sees some territories in Lithuania not belonging to it, like the capital Vilnius or the coastal city of Klaipeda. Estonia and Latvia expressed similar concerns to Karoblis. All countries increased their military budgets after the Crime annexation.

The Putin of the late 1990s and 2000s came across as idealistic and committed to building a functioning nation in comparison to Yeltsin’s anarchy.

Putin has, in the past, sworn ‘countermeasures’ to NATO expansion, of which the Baltic states are a prime example. The Baltics remain a point of conflict if only figuratively.

Baltics are a little skeptical about the West. They feel they can be a bargain in the deals of bigger powers.

Fear of Russian incursion into the Baltics very much varies from person to person and can be affected by various factors, including location, lineage, exposure to information, and professional role in society.

The threat from the East

The village of Stakai lies just past the narrowest point of the Lithuania-Belarus border.

Smuggling gangs operate all along the Baltic borderline. The practice is also an open secret in the Latvian town of Aluksne.

Activities of Russia in the Baltics are tests. They are testing new methods. As the world is focusing on Russia’s abilities in cyberattacks and misinformation, they are missing their ability to develop new methods of old-fashioned spying.

After the riots in 2007 in Estonia (started after the removal of Soviet monuments), the country was struck by a cyberattack that temporarily crippled banking, media, and government systems. Lithuania was attacked in 2008 and in 2016 – as did Latvia.

Energy networks were attacked in Ukraine but also in the Baltics.

Both Ukraine and the Baltics continue to be testing grounds for Russia.

Both Latvia and Lithuania are also locations in the top 20 worldwide, where cyberattacks started.

Russian success in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria is showing their military power. Baltics would have a hard time defending themselves, even with NATO’s help.

In the media war, Russian media in the country is constantly creating problems, talking about pressure on Russian people in the Baltics and creating misinformation.

The threat from the West

Russia is the world’s largest country, stretching across eleven time zones. Its mainland border with the Baltic states is only around 450 kilometers long.

The concept of heroism survives today as a major point of association in memorials, museum exhibits, and television to bolster the Russian state’s current steadfastly militaristic and patriotic narrative – but there is real emotion, hardship, and loss underpinning the simulacrum. In Russia’s eyes, the Soviet Union saved the world from Hitler. They had 95 % of the military causalities of the three major powers of the Grand Alliance.

Putin plays by different rules; indeed, for him, there are no inviolable rules, no universal values, not even cast-iron facts. There are only interests. His aim to restore Russia to a place of international prestige has remained consistent.

It is impossible to accurately assess Putin’s exact degree of popularity among Russians.

In 2008 NATO declared its intention to expand with Georgia and Ukraine. Soon after the Georgia war started. The fact remains, from where Russia is standing, NATO has been expanding its influence and edging closer to its borders.

Russians perceive the Baltics as essentially ‘Western’ or ‘European’. They seem to view Lativa with the most negativity, and Estonia as the most progressive or successful. The predisposition to view Lativa in a stereotypical negative fashion from inside Russia is the result of a variety of factors.

The Baltic states apparently consider being anti-Russian as their own defining characteristic. Russians were taught very little about the Baltic states in school.

In media RuBaltic media portal started in 2013 in Kaliningrad. It has published stories stating that ‘the Baltic states are pushing the US into a conflict with Russia’.

Vast swathes of Russian rhetoric apply feminizing language to the Baltics. The Western world is a child, a girl, someone to be easily overpowered and intimidated by displays of machismo.

Lithuanian academic Viktor Denisenko maps Russian media patterns since the Soviet collapse, identifying five key trends and one overall pattern in approaches to the Baltics. The overall pattern marked a distinctive change in tone from inside Russia. In the 2000s, the Russian press started classifying the treatment of the Baltic States as ‘Others’. Narratives of Russophobia and nationalism in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, as well as narratives suggesting violations of human rights and failed economies. Two further key spheres are security (NATO threat to Russia) and history (free will behind Baltic membership in USSR). The nature of depictions of the Baltic states in Russian media fluctuates depending on contemporary political currents.

Baltic Russians

Galina Timchenko and some twenty other journalists left Lenta in March 2014 to set up the Latvia-based Meduza. Russia’s free press in-exile.

Latvia is a country of two minorities – Latvians act like a minority even though they are the biggest part says Ivan Kolpakov. He feels sometimes that people there identify him as part of the Russian minority … and he doesn’t have any personal connections with the local Russian minority and community.

Alexander Morozov also recognizes a division between society’s Russians in his Baltic home. The old community of Russians that lived there for a long time and were born there. And the ones that come to Vilnius … after the beginning of Putin’s third term.

Lithuania is much safer for Russians than Latvia, on account of its much smaller Russian population, and less heated ethnic divide.

Estonian Narva is a city of 73 percent of the population being Russian. It is a city on a border, very well maintained. Much better than Ivangorod in Russia, which is only 4 km away. Local rumor is that the Estonian government is making sure that the city is well maintained to show the difference to Russian life.

The ethnic Russian and ‘native’ communities in both Estonia and Latvia are somewhat location-dependent. Lasnamae is a Russian-majority administrative district on the outskirts of Tallinn.

The linguistic issue is clearly at the forefront of the divide between ethnic Estonians and ‘native Russians’. Integration between the calcified communities is increasingly necessary.

Between 1989 and 2003 Russia saw a positive net migration of just over 243.000 people from its near abroad.

Historically, the Baltic coast was filled with spa and resort towns popular with Soviet citizens, even then as a ‘window to Europe’ of sorts. The most famous was Latvia’s Jurmala. Alisher Usmanov from Gazprom bought a property in Jusmala.

Latvia was suffering from money laundering and corruption. Highly dubious money has been gushing through Latvia since the Soviet collapse. Some 21 billion USD was transferred and cleaned from 19 Russian banks. The majority almost 14 billion went through Trasta Komercbanka in Latvia.

The Russian language is disappearing from the region. So are Russian schools.

It seems Russians in the Baltics see several positives to being in Europe and have a sense of nuance regarding their own presence in the Baltics.

The Baltic future

Baltic countries reject the term post-Soviet era.

In history the largely German Northern Crusades in the Baltic states aimed to Christianize these lands from around the twelfth century, and later Enlightenment Romanticist and nationalist trends depicted the Teutonic Knights and Livonian Order as part of a civilizing mission, spreading the German Kulturraum. By the end of the fourteenth century, German was overwhelmingly used in Riga and Tallinn, especially by the predominantly German-speaking aristocracy – largely the result of Ostsiedlung – that medieval German eastward expansion (not dissimilar to the more modern idea of Lebensraum), as well as the Teutonic Order’s campaigns.

A lot of good Latvian musicians are products of Soviet music schools.

Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, all have a strong tradition of song and dance festivals.

Fostering a connection to the land, old languages, old gods, and tradition is intrinsically linked to identity and community, and Baltic pagan religions have enjoyed a recent resurgence.

The ‘slow’ food scene in the region places a profound emphasis on the seasonal and the local often procured in person from the wild directly by restaurant staff.

Tallinn-based Starship company is producing beetle-like delivery robots. It was set up by the founding members of Skype.

While Estonia is a startup haven, Lithuania is geared more towards accommodating foreign companies. Vilnius Tech Park is the biggest ICT startup hub in the Baltics.

With all technological progress, the Baltic states are still socially conservative in several ways.

In the whole of the EU, the Baltics hold the proud position of the highest proportion of household expenditure on alcohol. The suicide rate in Lithuania is the highest in Europe.

The Baltics in Europe

The world is making a return to ‘Great Power’ politics.

Different blocs within Europe are beginning to form. One is the New Hanseatic League. Established in February 2018, it encompasses the Republic of Ireland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The coalition of fiscally conservative northern European governments developed in the wake of the UK’s Brexit crisis.

Russia certainly uses energy politics as a foreign policy tool in the region. Gazprom (natural gas), Rosneft (oil), and Rosatom (nuclear) are all sort of ambassador companies of the Russian government.

After the LNG terminal opened in Klaipeda, Lithuania, in 2015, Gazprom was finally edged out of the market.

Out of the three Baltic states, Estonia is faring the best economically. The banking sector in all three countries is generally dominated by Scandinavian subsidiaries.

The transition from old manufacturing is also underway.

Right-wing parties carry slightly more sway in Latvia and Lithuania than in Estonia.

Latvia and Lithuania are also fighting with outward migration.

Corruption is also an issue, especially in Latvia.

Conclusion

The Baltics can never quite forget the one simple fact: that Russia can militarily overpower the region. However, an invasion or outright conflict in the Baltic region remains an incredibly unlikely scenario at present.

Russia is using hybrid war, media communication of the backwardness of Baltic states, and narrative about the Soviets saving the Baltics from Hitler.

Division in Europe, such as Brexit and the rise of far-right nationalism may be exactly what Putin’s government seeks.